By: Robert J. Dougherty

Expect millennial workers to return (if they ever really left) to where they were raised

Much has been written about the so-called “Millennial” or “Generation Y” worker. Demographers have failed to pin precise dates on when this generation of people begins and ends, but generally the millennials are considered to be those born between the early-1980’s and the late-1990’s. The term “millennial” is believed to have been coined to refer initially to those graduating from high school around the turn of the millennium. Today, the millennial office worker ranges from those preparing to graduate college and take their place in the workforce to vice presidents in their mid-30’s.

Millennial workers are undoubtedly a powerful cohort in the U.S. labor market, representing the largest single generation employed today, so it is important for real estate investors to understand how their traits and desires will influence space utilization trends. Naturally, the millennial generation is heavily tech oriented and thoroughly plugged in online. They have also become tagged with a reputation for being entitled, needy, and self-centered. Whether or not these labels are appropriate is an assessment better left to the sociologists. However, the savvy real estate investor will seek to determine what this generation will demand from commercial and residential properties because, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, millennials will comprise nearly 75% of the U.S. workforce by 2030.

Flocking to the cities?

A widely held view in the real estate community is that millennials have migrated to U.S. central business districts (CBD’s) in droves, a trend which is believed to have accelerated as the economy emerged from recession in 2010-2011. Proverbially, the millennial worker emerged from his/her parents’ basement in Reston or Irvine (if Irvine had basements) and found a job again – some for the first time. Attracted by the vibrant arts and social scenes that downtowns offer, America’s professional youth took up residence in flats from New York to San Francisco and showed up to their desks in DC and Los Angeles. These children of the suburbs were becoming urbanites.

Of course, the last two sentences above could have been written as accurately in 1972, 1987, and 2002. Twenty-something’s have gravitated towards cities for generations, maybe even centuries. Data does, in fact, illustrate that younger Americans are more urban-oriented [chart] than their elders, but does this come as any surprise? Are they more city-loving at their current ages than their parents were 30 years ago?

towards cities for generations, maybe even centuries. Data does, in fact, illustrate that younger Americans are more urban-oriented [chart] than their elders, but does this come as any surprise? Are they more city-loving at their current ages than their parents were 30 years ago?

Some say yes. They believe that millennials are, in fact, signaling an important demographic shift towards urbanity. Being connected to a large online social network, they value integrated community living, as well. They are concerned about their carbon footprint so they shun the automobile in favor of mass transit and laying down actual footprints on city sidewalks. They crave the pedestrian lifestyle of the corner coffee shops that they knew in college and look forward to posting on Instagram or Snapchat about dining at the hot new restaurant in town and hitting the coolest clubs afterward.

The real estate corollary is that absorption of office space since the Great Recession has favored CBD’s over the suburbs. Conventional wisdom holds that employers were forced to compete for talent as the economic recovery took root, compelling them to rent downtown offices in order to attract millennial workers living nearby. Ping pong tables, bike lockers, wired internet lounges, and stocked cantinas . . . even climbing walls and massage rooms became necessary accoutrements for drawing in the desired millennial worker pool.

compete for talent as the economic recovery took root, compelling them to rent downtown offices in order to attract millennial workers living nearby. Ping pong tables, bike lockers, wired internet lounges, and stocked cantinas . . . even climbing walls and massage rooms became necessary accoutrements for drawing in the desired millennial worker pool.

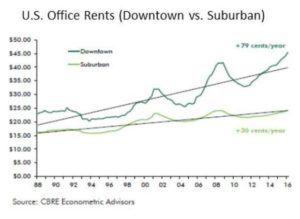

So goes the accepted narrative. But is it accurate and does it tell the whole story? Consider that companies may have chosen to rent space in the CBD’s as their employment needs expanded because it was comparatively cheap coming out of the recession. The dramatic rise in office rents that has been witnessed recently really began in 2014. From 2009 – when landlords would have given away space if they had any takers – through 2013, downtown office space was comparatively inexpensive on a constant-dollar basis versus historical rents. Of course, suburban space was even cheaper but, if one can get a Lexus for the price of a Toyota, the “luxury” choice is often made. Maybe accommodating workers’ desires was secondary to cost considerations in companies’ expanding downtown?

rise in office rents that has been witnessed recently really began in 2014. From 2009 – when landlords would have given away space if they had any takers – through 2013, downtown office space was comparatively inexpensive on a constant-dollar basis versus historical rents. Of course, suburban space was even cheaper but, if one can get a Lexus for the price of a Toyota, the “luxury” choice is often made. Maybe accommodating workers’ desires was secondary to cost considerations in companies’ expanding downtown?

But will they stay?

Some sociologists are debunking the notion that millennials are more city-loving than generations which have preceded them. For instance, demographer William Frey argues that many millennial workers have mentally “aged out” of the cities in which they dwell. However, they’ve been “trapped” downtown as victims of economic circumstance since the Great Recession. Declining real wages, poor job prospects in a tepid recovery, and a larger load of student debt than any prior generation have left millennials unable to afford to buy homes in suburbia. Even those whose fortunes have improved in the latter stages of the current job expansion may have missed their window to buy an affordable home in the suburbs given the sharp rebound in housing prices in major U.S. metropolitan areas.

But are millennials really pining for the “home with a white picket fence?” Perhaps the younger generation does not covet home ownership to the same degree their parents did. This thinking argues that millennials would rather rent in the cities versus buying in the suburbs. (Buying in the cities has basically become a “one percent” proposition.) Proponents of this view point to a rate of U.S. home ownership that reached a 50-year low of 63.1% in the second quarter of 2016 and, more particularly, the low rate of home ownership amongst persons aged less than 35 years – 34.1% as of 2Q16 according Census Bureau data. The latter rate has also declined markedly in recent years. At the end of 2010, the ownership rate amongst sub-35 year-olds was 39.2%, so it has fallen off over 500 bps while home ownership for all Americans declined only half as much, by 260 bps, from 80.5% to 77.9% over the same period.

However, the preponderance of research seems to run contrary to the reputation of the city-loving millennial. One researcher recently wrote, “Millennials presence in the city should not be confused with a preference for the city.” Nearly all consumer surveys indicate that Americans still greatly desire home ownership. For example, a recent survey conducted by the National Association of Realtors (NAR) indicated that 87% of Americans believe that home ownership is part of the American Dream, and a similar survey by Ipsos asked consumers if they agreed with the statement that home ownership is a dream come true … 86% agreed. Instead, it seems far more likely that the decline in home ownership across the board and amongst millennials has much more to do with the inability to afford a home versus lacking desire to own one.

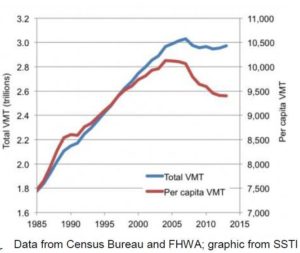

In fact, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 78% of households earning above the national median income owned their homes while only 48% earning below the median were home owners at the end of 2Q16. The Great Recession put a major dent in potential down payments of many would be home owners. Despite historically low interest rates, some have yet to see their incomes fully recover enough to afford the ongoing mortgage service. Reduced wealth – households headed by persons younger than 35 years saw a 30% decline in net worth between 2010 and 2015 – is causing many life decisions to be delayed out of necessity and adds to the notion that some millennials are stuck in the cities. Marriages are happening later in life amongst the younger set, and millennials are far less likely to possess a car or a driver’s license than prior generations. The latter presents a conundrum. Some don’t own cars by choice because it’s expensive and unnecessary in America’s largest cities, but those who can’t afford to own a car are truly beholden to urban dwelling.

Still other potential buyers are saddled with credit problems and debts racked up during the recession and face a more stringent lending environment in which banks and other mortgage lenders are far choosier in selecting borrowers and documenting qualifications. One-third of millennials fail to satisfy the minimum average credit score of 620 which Fannie Mae requires for mortgage purchases, making it difficult to obtain a conventional home loan.

Nonetheless, time heals all wounds, and America remains a society that values and promotes home ownership. It is engrained in our national ethic, embodied in our financial system, and codified through material benefits in federal tax laws. As the bank accounts of millennials eventually recover and as they age and expand families with more children of their own, it is reasonable to expect that they will seek to plant deeper roots just as their parents did. But where will they settle down?

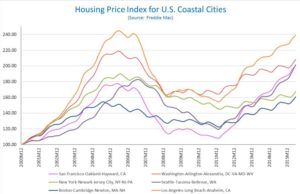

If one accepts affordability as the principal impediment to home ownership, then it’s hard to believe that family roots will be established under city streets. According to a recent study by Zillow, homes located in urban U.S. ZIP codes appreciated by an average of 7.5% in 2015, while suburban homes appreciated 5.9%. Over a five-year period, between 2010 and 2015, city homes are up 28.4% compared with 21.1% growth in suburban home prices. Notably, the differential is much more pronounced in America’s largest cities, especially coastal markets. In Los Angeles, the value of urban homes rose a whopping 42.1% between 2010 and 2015, while homes in LA’s suburbs appreciated by 33.9% over the same time frame. A similar story has played out over the past 5 years in Boston (37.1% city home price growth vs. 20.5% in the suburbs), Washington, D.C. (23.8% vs. 14.4%) and San Francisco (65.3% vs. 58.7%).

How can the typical millennial, who has faced declining household wealth afford a home in the heart of San Francisco when it costs 65% more than it did in 2010? Furthermore, if a buyer still values space, it is also worth noting that city homes are getting smaller at the same time that they’re getting more expensive. In Washington, D.C., for example, urban homes in 1996 cost 6% more per square foot than suburban homes. In 2015, they cost 41% more per square foot.

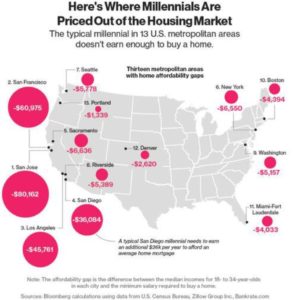

A case can be made that this increase in urban home prices, particularly in America’s largest coastal cities, needs to be viewed through the lens of rising income, which is taking place in major U.S. cities even while income growth is tepid across the country as a whole. Housing affordability is more important to assess than absolute pricing. However, the nation’s largest coastal cities also remain challenged in terms of price-to-income ratios. As the chart below reflects, East Coast metroplexes Boston, New York, Washington, and Miami all have price-to-income ratios above the national mean. San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle all tell a similar story of challenging affordability on the West Coast, as well. Granted, these ratios are well-below the credit-fueled bubble of 2005-07; however, with fewer cheap mortgages available except to the most creditworthy clients, true “affordability” may be worse even while price-to-income ratios are lower. [it should be noted that the map reflects the entire metropolitan areas, both suburbs and downtowns. The available data does not allow one to determine whether downtown incomes have kept pace with the rapid rise in city prices].

Evidence is mounting and more articles are being written which suggest that the reputation of the city-loving, permanently renting millennial may be apocryphal. Given that millennials seems to harbor home ownership aspirations, and the cities in which they are living are unaffordable, is their return to the suburbs preordained?

Reverse migration has begun

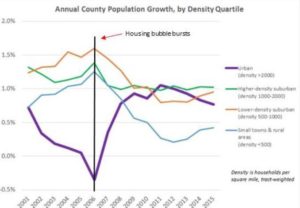

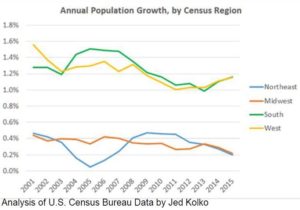

Actually, it appears that millennials have already commenced a return to the land of their upbringing. Population statistics released by the Census Bureau at the end of 2015 show a continued outmigration to the suburbs. In fact, the ballyhooed urbanization of America may have been nothing more than a blip or, at the most, a short-lived trend. Census data indicate that growth in urban areas was greatly outpaced by suburban population increases during the mid-2000’s housing bubble, as rising suburban home construction attracted buyers from all walks of life.

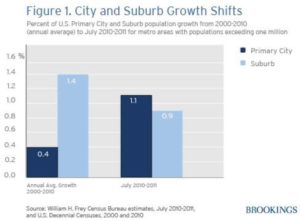

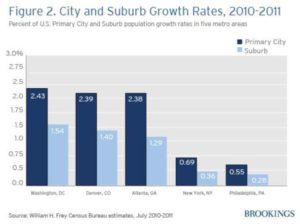

Emerging from the financial crisis, both suburban and urban areas gained population. The supposed preference for u rbanity seems to have been drawn from the slowing of a decades’ long trend of suburbanization. The differential in the rate of population growth between U.S. cities and their outskirts narrowed markedly after the housing bubble popped. However, only in one year – 2011 – did the population in cities actually grow faster than in the suburbs, and in 2015 urban growth actually slowed to its lowest level since 2007.

rbanity seems to have been drawn from the slowing of a decades’ long trend of suburbanization. The differential in the rate of population growth between U.S. cities and their outskirts narrowed markedly after the housing bubble popped. However, only in one year – 2011 – did the population in cities actually grow faster than in the suburbs, and in 2015 urban growth actually slowed to its lowest level since 2007.

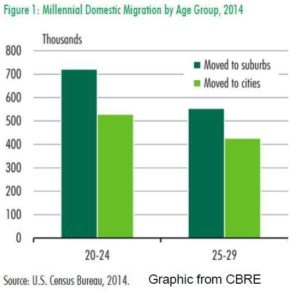

CBRE analyzed the Census data and concluded that approximately 30% of millennials reside in cities but noted that “the other 70% do not appear to be rushing to move  downtown.” CBRE also pointed out that so-called “midrange” U.S. millennials – age 25 to 29 – migrated more frequently from the cities to the suburbs (529,000) in 2014 than into downtowns (426,000). This outmigration was even more pronounced for persons 30 to 44 years of age. In 2014, 1.2 million of them left cities for the suburbs while only 540,000 headed in the opposite direction.

downtown.” CBRE also pointed out that so-called “midrange” U.S. millennials – age 25 to 29 – migrated more frequently from the cities to the suburbs (529,000) in 2014 than into downtowns (426,000). This outmigration was even more pronounced for persons 30 to 44 years of age. In 2014, 1.2 million of them left cities for the suburbs while only 540,000 headed in the opposite direction.

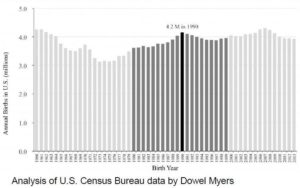

This suburban trend is more likely to grow than abate because the population peak of the millennial generation has not yet reached prime home buying age. Sociologists peg 1990 as the peak birth  year for the millennial generation. While this ignores the impacts of immigration, U.S. births did decline markedly after 1990. Thus, the peak millennials are now 25 years of age and will be “maturing” economically into potential homebuyers over the next 10-15 years.

year for the millennial generation. While this ignores the impacts of immigration, U.S. births did decline markedly after 1990. Thus, the peak millennials are now 25 years of age and will be “maturing” economically into potential homebuyers over the next 10-15 years.

Many demographers believe that the credit and housing bubble substantially distorted U.S. migration trends. Massive homebuilding fueled growth in the suburbs during the mid-2000’s. After the crash, America experienced a migration into the cities in search of higher paying jobs and more plentiful rental housing during the depth of the recession. The developing school of thought is that, now that the effects of the housing bubble are becoming normalized, the U.S. is reverting to its inexorable 60-year-old suburbanization trend.

Will the jobs follow? As with the millennials, they already are . . .

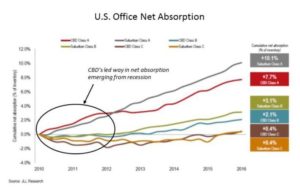

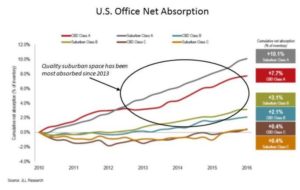

Of course, just because more heads are resting on suburban beds, doesn’t mean that jobs are also migrating to the suburbs. However, the post-recession trends in office absorption seem to mirror the population trends outlined above. Emerging from the global financial crisis, America’s downtowns enjoyed their day in the sun. From the beginning of 2010 through mid-2012, Class A CBD space led all categories of space in the rate of net absorption relative to inventory.  Notably, the flight to quality referenced above was also in evidence, as only Class A space – whether urban or suburban – enjoyed positive absorption in 2010 and 2011. However, since late-2012, suburban Class A space overtook all other office categories as the relative net absorption leader and has remained the leader since.

Notably, the flight to quality referenced above was also in evidence, as only Class A space – whether urban or suburban – enjoyed positive absorption in 2010 and 2011. However, since late-2012, suburban Class A space overtook all other office categories as the relative net absorption leader and has remained the leader since.

Of course, higher office space absorption in the suburbs has likely been a function of greater availability. In fact, suburban office buildings of all quality levels (Class A, B, and C) continue to remain less occupied than their downtown counterparts. However, expect  this occupancy differential to narrow as CBD office space becomes increasingly expensive. As the chart below illustrates, cumulative rent growth since 1Q 2010 for downtown Class A office space (29.0%) has been more than double that of Class A suburban space (14.4%).

this occupancy differential to narrow as CBD office space becomes increasingly expensive. As the chart below illustrates, cumulative rent growth since 1Q 2010 for downtown Class A office space (29.0%) has been more than double that of Class A suburban space (14.4%).

As Class A CBD office rents continue to reflect a rapid ascent, the overall gap between CBD and suburban rents has widened to a post-recession high.  According to Jones Lang LaSalle, CBD office rents were 62% higher than overall suburban rents at 3/31/16. If the U.S. economy softens, will belt-tightening cause employers to look more closely at this rent differential? If their workers are increasingly moving to the suburbs, perhaps relocating more jobs nearby would carry a “double bottom line” of lower costs and improved employee morale. This seems, if not inevitable, more likely than not.

According to Jones Lang LaSalle, CBD office rents were 62% higher than overall suburban rents at 3/31/16. If the U.S. economy softens, will belt-tightening cause employers to look more closely at this rent differential? If their workers are increasingly moving to the suburbs, perhaps relocating more jobs nearby would carry a “double bottom line” of lower costs and improved employee morale. This seems, if not inevitable, more likely than not.

Winners and losers . . . implications for commercial real estate

What will be the effects of this emerging suburban “renaissance” and what strategies can smart real estate investors employ to take advantage of it? The following are a few possible takeaways:

Cities with a high quality of life, strong employment growth, yet more affordable housing should benefit from long-term migration trends. Austin, Denver, Dallas, Atlanta, Charlotte, and Phoenix have already experienced this type of growth, seemingly at the expense of places like Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. However, don’t be surprised if growth slows in high-cost Tier I markets and the second-tier Western and Sunbelt cities begin to siphon people from Boston, New York, and Seattle, too.

Cities with a high quality of life, strong employment growth, yet more affordable housing should benefit from long-term migration trends. Austin, Denver, Dallas, Atlanta, Charlotte, and Phoenix have already experienced this type of growth, seemingly at the expense of places like Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. However, don’t be surprised if growth slows in high-cost Tier I markets and the second-tier Western and Sunbelt cities begin to siphon people from Boston, New York, and Seattle, too. parents to be concerned about their cars’ emissions contributing to climate change. They are likely to place a higher value on the option of public transit. Additionally, even if their job has followed them from downtown or they found a new position in the suburbs, many millennial suburbanites will have left friends, dentists, hairdressers, or their favorite bars and yoga instructors in the city. They will value a convenient commute. Lastly, a few die hard urbanites simply won’t be able to bring themselves to leave the city. In this case, placing employment centers near public transportation will allow the city dwellers to reverse commute to jobs in the suburbs. This is a phenomenon that is growing more abundant.

parents to be concerned about their cars’ emissions contributing to climate change. They are likely to place a higher value on the option of public transit. Additionally, even if their job has followed them from downtown or they found a new position in the suburbs, many millennial suburbanites will have left friends, dentists, hairdressers, or their favorite bars and yoga instructors in the city. They will value a convenient commute. Lastly, a few die hard urbanites simply won’t be able to bring themselves to leave the city. In this case, placing employment centers near public transportation will allow the city dwellers to reverse commute to jobs in the suburbs. This is a phenomenon that is growing more abundant. These factors have resulted in a 15-year record price gap between urban and suburban office properties. Although it appears that downtown office buildings have outperformed their suburban counterparts, their price volatility has been more severe. Furthermore, given the dramatic post-recession appreciation in CBD assets, what will drive further price increases? It is hard to fathom cap rates declining further. Also, if the millennial workers are looking to abandon the city at the same time that new buildings are being constructed to house them, can one rely upon income gains from downtown properties? In the same manner that demographics appear to be reverting to long-term prevailing trends, suburban commercial properties are a safer bet, banking upon a reversion to historical norms through a narrowing of the price gap to more typical levels.

These factors have resulted in a 15-year record price gap between urban and suburban office properties. Although it appears that downtown office buildings have outperformed their suburban counterparts, their price volatility has been more severe. Furthermore, given the dramatic post-recession appreciation in CBD assets, what will drive further price increases? It is hard to fathom cap rates declining further. Also, if the millennial workers are looking to abandon the city at the same time that new buildings are being constructed to house them, can one rely upon income gains from downtown properties? In the same manner that demographics appear to be reverting to long-term prevailing trends, suburban commercial properties are a safer bet, banking upon a reversion to historical norms through a narrowing of the price gap to more typical levels.

Conclusion

All in all, it appears that the conventional wisdom that millennials are initiating a permanent trend towards urbanization is too simplistic and overblown. While it is clear that metrocentric millennials have sparked a resurgence of the urban core, the idea that they’ve permanently forsaken the suburbs doesn’t jibe with the data or stand up to closer scrutiny. CBRE speculates that the notion that downtowns are surging while the suburbs are sinking derives from recent trends in several high-profile cities such as Washington, DC and San Francisco, along with the few anomalous post-recession years in which downtowns actually did outperform their outskirts. The pendulum swings between the suburbs and the city, often in keeping with the economic tides. It is now swinging back in favor of the ‘burbs’. Perhaps it will swing less far this time, but the savvy investor will recognize and benefit from these evolving demographics.

###